Wadi Hammamat Hurghada information, tours, prices and online booking

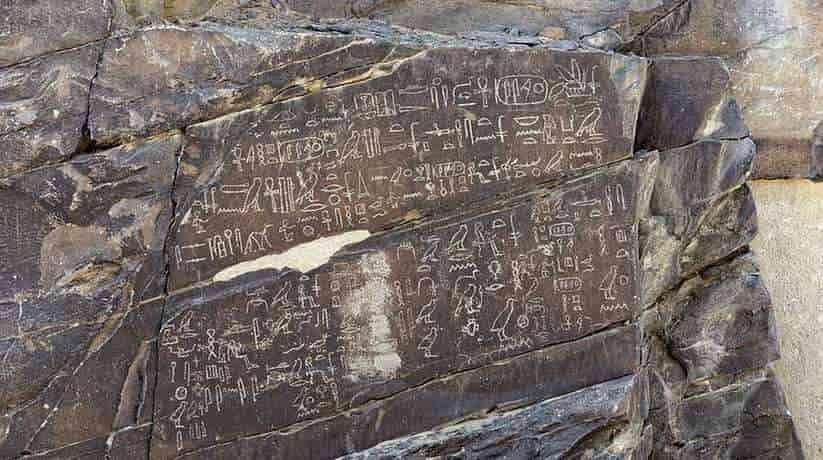

Wadi Hammamat Hurghada is one of a great number of dry river beds. In fact, it wind through the rugged mountains of Egypt’s Eastern Desert and the modern road. The road in fact runs through Qift (Greek Coptos) to the port of El Quseir on the Red Sea. The route used for millennia as a trade route from the Coast to the Nile. Moreover, the area also famed for its quarries and gold mines. In fact, the area features scores of ancient ruins which line the route and remains of watchtowers. Furthermore, it also features forts, wells and mines from various periods. In fact, they show much evidence of ancient quarrying and mining activity. The valley perhaps best known for its hundreds of hieroglyphic and hieratic rock inscriptions.

In fact, they record the activities of expeditions which sent by many kings. The expeditions in fact sent to obtain the precious resources of bekhen-stone. The stones used for small-scale building projects, sarcophagi, statues and vessels during the Pharaonic Period. There is evidence in the area of prehistoric man, desert dwellers and nomads. The nomads who left crude petroglyphs bruised into the rocks in the form of curved reed boats, hunters and long-gone animals, including elephants and ostriches, suggesting that the desert was at that time a more hospitable place. This route through the mountains of the Eastern Desert taken by travelers and expeditions from the Old Kingdom onwards, right through to the Romans.

More information about Wadi Hammamat Hurghada:

The Romans in fact exploited the quarries and gold mines the most, and who built stone watchtowers on the tops of the hills to guard the road and the wells. Wadi Hammamat Hurghada contains a variety of sandstone, greywacke and schist-type rocks. In fact, they all known as Bekhen-stone in ancient times. The colors of the rocks vary from a very dark basalt-like stone. It is through reds, pinks and greens. Although this stone was usually too flawed for building large monuments, it highly prized for palettes. In fact, it was also the same for statues, sarcophagi and smaller shrines. The Turin Papyrus mining map, thought found by Drovetti at Deir El Medina. It now reconstructed in the Museo Egizio in Turin. In fact, it is the oldest topographical and geological map known from Egypt.

Moreover, it drawn by a scribe named Amennakhte, son of Ipuy. In fact, he commissioned to make the map during an expedition of Ramses IV. He is the king who sent one of the largest recorded quarrying expeditions to the Wadi Hammamat. The map shows part of the route through the valley and depicts identifying features. In fact, the features are such as hills, together with distances between quarries and mines. The use of different colors and textures for the different features with a descriptive legend was very innovative. The Bekhen quarry on the northern side of the road still contains remains of workmen huts. In fact, they built from the dark schist stone and nestled in the lee of the cliff. Quarry marks can seen everywhere and halfway up the cliff there is an abandoned sarcophagus.

Further information about the site:

It perhaps split or fractured during quarrying. On the southern side of the road the cliffs littered with inscriptions left by expedition members. In fact, many of which can dated to the year of the reigning pharaoh. They provide invaluable historical records of the activities of a long line of kings. One of the earliest pieces of evidence of the use or exploitation of the Wadi Hammamat may be a graffito. In fact, it contains a serekh of the Early Dynastic King Narmer. It inscribed on a rock in the Wadi El Qash, an offshoot of the Wadi Hammamat Hurghada. The Wadi Hammamat known to use during Dynasty VI and probably earlier. In fact, it used as a route to the Red Sea and from there to the East African coast and the Land of Punt.

Texts that dated with accuracy point to possibly several expeditions sent by Pepi I. In fact, it was to extract blocks of bekhen-stone for temple statuary. An undated graffito also shows the presence of an expedition of Merenre, the last Old Kingdom pharaoh to be featured here. Quarrying and military activities account for the majority of inscriptions from the Old Kingdom and the names of other kings briefly mentioned in graffiti include Khufu, Khafre, Djedefre, Menkaure, Sahure and Unas. Also thought to date from the Old Kingdom is a curious text of an official Zaty, named as ‘King’s Son’ and ‘General’ in the reign of an unknown king Imhotep. The First Intermediate Period was a time of upheaval in the whole of Egypt with a decline in the state’s economy and political structure.

More details about Wadi Hammamat Hurghada:

Though there are a couple of small graffiti mentioning Merykare and Ity, Herakleopolitan rulers of Dynasty X. It seems to be Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II of Dynasty XI. He re-opened the Wadi Hammamat route and possibly sent quarrying expeditions there. In fact, it was at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom and a short hieroglyphic graffito most probably dates to his rule. His son, Sankhkare Mentuhotep III sent a large expedition of 3000 men in Year 8 of his reign. In fact, it attested by a text of his Chief Steward Henenu. The purpose was to establish a trade contact with Punt, but they may also have done some quarrying. In the final recorded Dynasty XI journey, Nebtawyre Mentuhotep IV sent an even larger expedition in Year 2 of his reign. In fact, it shown in four large rock-stelae.

We told by Vizier Amenemhat (probably the later Pharaoh Amenemhat I) how their mission was to quarry bekhen-stone. In fact, it was for the King’s sarcophagus. We also told how a gazelle gave birth on the block they chosen. An auspicious omen greatly encouraged the workforce of 10,000 men. Another of Vizier Amenemhat’s texts records the ‘wonder of rain’, a flash flood that produced a well of clear water. Most of the Middle Kingdom texts in the Wadi Hammamat Hurghada are long. They also include dedications to the local god, Min of Coptos, his consort Isis and their son Horus. They in fact depicted receiving offerings. A cartouche of the king usually inscribed. It is along with the year of the reign and name of the expedition leader. They often give details of the mission.

Further details about the site:

Dynasty XII begins with the Pharaoh Amenemhat I, who left a single undated rock-stela in the Wadi Hammamat. His son Senusret I sent missions there in reignal years 2, 26 and 38. In fact, the third was the largest ever to work in the wadi. A team of roughly 18,660 skilled and unskilled workers had the task of quarrying stone for 60 sphinxes and 150 statues. They included soldiers, hunters, brewers, bakers and of course the scribes, artisans and laborers, . Two large rock-stelae date to this expedition. In fact, they give names of personnel and even the rations that issued. Later Middle Kingdom rulers attested here include Senusret II and III. Each sending a single mission and Amenemhat III. In fact, he sent at least four expeditions in years 2,3,19 and 20 of his reign.

First discovered in 1950 and thought to be an Old Kingdom text. But more likely dating to the Middle Kingdom, a brief, crudely-worked. In fact, it is important graffito constitutes one of the earliest king-lists. Moreover, it written by a minor official which names Old Kingdom rulers Khufu, Djedefre and Khafre. In fact, it written in cartouches. The author of this unusual inscription also includes the names of Princes Hordjedef and Bauefre in cartouches. The chronology at the end of the Middle Kingdom into the Second Intermediate Period is difficult to ascertain. In fact, the period represented in the Wadi by a stele of Sobekhotep IV Khaneferre. It is while there were possibly two or three graffito naming King Sobekemsaf I Sekhemre-wadjkhau.

More details about Wadi Hammamat Hurghada:

There are surprisingly few texts from New Kingdom Pharaohs. In fact, they are among the rock-inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat Hurghada. It is perhaps because a more northerly route may also used to cross the Eastern Desert at this time. Names and titles recently found representing Ahmose I and Amenhotep II. In fact, the two brief texts of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) found there. They are more interesting historically as they both mention a high priest of Amun. In fact, Amun sent to collect bekhen-stone. Presumably this was from the king’s early reign while the Theban priesthood were still in favor. Though, the wadi likely continued to be used during Dynasty XVIII, no evidence of other rulers have been found.

In Dynasty XIX, Seti I usurped a relief of Amenhotep IV. It shows the king kneeling with two vases before Amun-re. Moreover, it also shows two more images of Seti I which offering Ma’at and flowers to Amun-re. Seti II also represented in a relief and a stela. It was by the Vizier Paraemheb in which the king is in the presence of Min, Horus and Isis. In fact, the long reign of Ramses II represented by only one set of cartouches in Wadi Hammamat. The most prolific New Kingdom Pharaoh was undoubtedly Ramses IV Hekamaatre Setepenamun of Dynasty XX,. Its inscriptions dated to four missions during the first three years of his reign. They describe expeditions which sent to procure stone for his Theban monuments.

Further details about the site:

Stelae inscribed by several priests and officials describe the expeditions of Ramses IV. Moreover, here are many minor graffiti dating to the reign. A text of Turu, high priest of Montu, dates to Year 1. In fact, it depicts the king in the presence of many deities. It is while a stela dating to Year 2 mentions the extracting of bekhen-stone for the ‘Place of Eternity’. In fact, the largest mission was in Year 3. It is when Ramesesnakht, high priest of Amun, sent with a large workforce to quarry stone for the “Place of Truth”. He recorded on two stelae. This was the expedition that produced the Wadi Hammamat mining map.

The only Third Intermediate Period ruler to be mentioned here is the Theban High Priest Menkheperre of Dynasty XXI. This was another period of economic decline and political disruption in Egypt. In fact, the expeditions were not documented again. It was until Dynasty XXV and XXVI. A text by a quarryman, Psenuenkhons, recorded from the time of the Divine Adoratrice Amenirdis I, Year 12 of King Shabaqo. Cartouches and graffiti relating to Taharqa, Psamtek I, Necho II and Psamtek II also found. Graffiti dating to the First Persian Period occupation are particularly numerous. They seem to represent a new level of activity in the Wadi Hammamat. With the exception of Darius II, all of the major Persian kings are represented here.

More details about Wadi Hammamat Hurghada:

One very important graffito from this time inscribed high on the sloping cliff-face. It is by Khnemibre, ‘Superintendent of Works in Upper and Lower Egypt’. The name written in a double-plumed cartouche. Khnemibre was a Royal Architect who held office during the reigns of Amasis and Darius I. This inscription written as a genealogy dating backwards from Khnemibre’s father, Ahmose-saneit. In fact, it is over 22 generations of Royal Architects to Rahotep, a Vizier of Ramses II. Khnemibre himself depicted standing before the goddess Hathor and the text is dated Year 26 of Darius. David Rohl and other revisionists used this inscription to illustrate their arguments for the shortening of the Third Intermediate Period. In fact, it challenges the bases of the traditional Egyptian chronological framework.

The latest hieroglyphic inscriptions in the Wadi Hammamat date to the reign of Nectanebo II of the Dynasty XXX. In fact, there are also many demotic or Greek texts from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. The Romans brought renewed interest in the wadi. It is especially as a trading route, building watchtowers and signal posts, forts and a fortified well at Bir Hammamat. In the bekhen-stone quarries, a temple containing several side-chambers dated to the time of Tiberius by an inscribed naos. Graffiti in the wadi records activity under Emperors Augustus, Nero, Titus, Domitian, Antoninus and Maximinus. Bir Hammamat was a Roman fort and major watering station for travelers through the wadi. The stone walls can still seen, built to protect the well, 34m deep, which had a winding staircase to the bottom.

Further details about the site:

This is a great feat of Roman engineering and impresses on the visitor the vital importance of water in this arid landscape. The first European descriptions of the Wadi Hammamat were from the Scottish traveller James Bruce in 1769. Though he made no mention of the inscriptions. Sir John Gardner Wilkinson and Lepsius visited the wadi during the 19th century. The Russian Egyptologist Vladimir Golenishchev led the first modern study of the inscriptions. It was in 1884-1885.Bbut it was not until the early part of the 20th century. More interest was shown in the site by Arthur Weigall in 1909. In 1912 a thorough survey undertaken and published by Couyat and Motet.

Moreover, in the 1930s the German pioneer Hans Winkler thoroughly explored the area. In fact, it was by camel before world war II interrupted his work. He recorded the desert boats, which never completed before his death. Wendorf and Schild explored the Eastern Desert regions, publishing their results in 1980. Susan and Donald Redford, Gerlad Fuchs, David Rohl conducted the Eastern Desert Survey. Mike and Maggie Morrow published RATS (Rock Art Topographical Survey) are just some of the latter-day explorers of Wadi Hammamat.

How to get there:

In fact, the distance between Qift and El Quseir is 180km. Moreover, the ancient road beginning at the Roman watering station at Laghieta is about 50km from the turnoff south of Qift. After 83km, there is a narrow defile just as the road begins. It is to pass between the higher mountains and where the scenery gets more spectacular with every kilometer. A little way past an ancient well known as Bir Hammamat to the northern side of the road. In fact, the road narrows into a rocky gorge. It is between high, dark, jagged mountains towards Bir Umm Fawakir. This is where the concentration of a large number of rock inscriptions can found.

There is a small gafir’s hut opposite the inscriptions. At the entrance to Wadi Fawakir (108km) there is a coffee shop. It is where travelers can stop for refreshments. A special permit now required from the SCA to stop at the site of the graffiti and all photography is banned.